Thirty-eight miles from where I live in Newnan, Georgia is the land my third great-grandfather, Samuel Lee, owned in the 1800’s. This Henry county property has an interesting history. Before my ancestor settled it, Creek Indians and fur traders lived off of it by hunting, fishing, and trapping. By the start of the Civil War, my forebearer had already cleared the woods and put a farm and sawmill on it.

After Samuel’s death, the land changed hands within three more generations of his family until it was purchased by Lion Country Safari-Atlanta in 1970. Many tourists remember visiting this attraction. I am sure my third great-grandfather would have never imagined the day (1970-84) when cars would drive through his farmland to observe lions, giraffes, and elephants roaming freely.

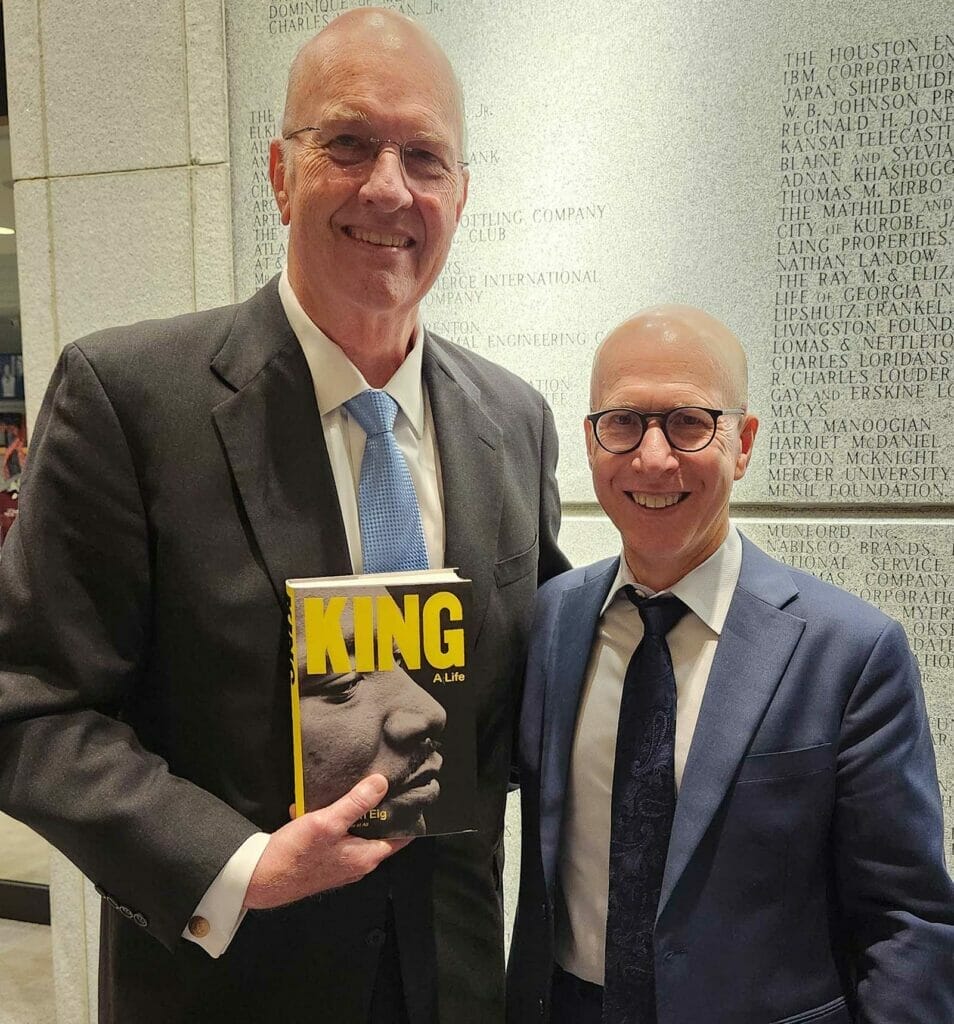

Nor could Samuel Lee have foreseen that his homestead would, one day, be worked by the grandparents and father of one of our nation’s most well-known religious and political leaders, the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I did not know this fact until I was contacted by Chicago Tribune writer and best-selling author, Jonathan Eig. His latest work is King: A Life, a biography about MLK (published May 16, 2023).

Through a genealogical researcher, Eig discovered my connection to MLK. He informed me that Samuel Lee’s great-granddaughter and her husband continued to farm my forefather’s land in the early 1900’s, and used sharecroppers to work it, some of whom were the family of MLK’s grandfather, Jim King (The Weekly-Advertiser, McDonough, Georgia, February 12, 1970) .

I was grieved to learn that MLK’s father was mistreated on my ancestor’s property. Stanford University’s The King Papers (1:2) tells how MLK’s father, “Mike”, about 12-years-old around 1910, was passing by the sawmill, one summer day:

(The owner of the sawmill) demanded that King get a bucket of water for the sawmill workmen. The youngster politely declined, whereupon the white man beat him . . . Mike ran home and explained what had happened. His enraged mother then returned to the mill with her son to confront the owner; when he acknowledged he hit the boy, she knocked him down and pummeled him. Jim King, upon hearing of the incident, took his rifle to the mill and threatened to kill the man. That evening, white men mounted on horses visited the King house in search of Jim King. Having heard they were after him, however, King had already fled. He lived for months in the woods and by the time tempers had cooled enough for him to return to his family, he was drinking heavily . . . (page 8).

When Eig told me this sad story, it opened the opportunity for me to inform him about my work toward racial reconciliation in our community and an article reporting on it in The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/19/us/newnan-art-georgia-race.html.

Learning about this and my ancestor’s ownership of the mill where discrimination toward MLK’s father occurred, Eig asked if I would sit for a future podcast and possible documentary interview at that site with Dr. King’s nephew, Isaac Newton Farris, Jr., former president and CEO of the King Center. I agreed.

Pray that I can use this opportunity to share that the gospel is the truest hope for racial harmony. I also wish to promote the Unify Project, a new national grassroots racial unity initiative released in cooperation with the Southern Baptist Convention in November of 2022 http://theunifyproject.org. Only Christ can make us one (Galatians 3:28).